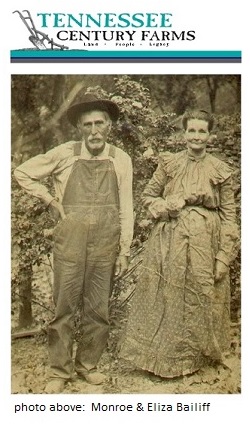

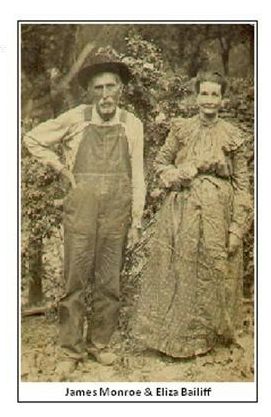

J.M. Bailiff Farm

The Early Years

James Monroe Bailiff (farm founder) descended from Pennsylvania Quakers. Tax records show Monroe’s great grandfather, Thomas Bailiff, in Chester Co, Pa as early as 1747. His grandfather, Thomas Bailiff, Jr., relocated from Pennsylvania to Orange Co, North Carolina during the 1790’s and eventually to Temperance Hall, Tennessee in DeKalb County [Smith County at the time] about 1820. Monroe’s father, Isaac Bailiff, was a member of the Masonic Lodge and learned the skills of a blacksmith from his father. And, Smith County property tax records from 1837 and 1838 indicate the family owned slaves and paid taxes on such.

Isaac Bailiff married Monroe’s mother, Nancy Bates, on December 13, 1831. She was the daughter of Isaac Bates and Didama Tubb. Isaac was a slaveholder, and Didama was the older sister of Colonel James Tubb of Liberty, a slaveholder and officer in the Union Army during the War for Southern Independence. The wedding was an affair and was announced in the “National Banner” and “Nashville Whig” publications in Nashville.

Isaac Bailiff married Monroe’s mother, Nancy Bates, on December 13, 1831. She was the daughter of Isaac Bates and Didama Tubb. Isaac was a slaveholder, and Didama was the older sister of Colonel James Tubb of Liberty, a slaveholder and officer in the Union Army during the War for Southern Independence. The wedding was an affair and was announced in the “National Banner” and “Nashville Whig” publications in Nashville.

Monroe was born on December 2, 1845 at Temperance Hall. He was the sixth of eight children born to his parents. He enlisted in the Confederate Cavalry on February 25, 1863. He served in Company A of Allison’s Battalion along with his brother, Columbus Bailiff. He was shot during the Battle at Chickamauga on the second day (September 19, 1863) of the fighting.

Monroe told his grandson, Charlie F. Bailiff (1911-2001, 3rd owner of the J.M. Bailiff Farm), that he was horseback, riding a mare that he had brought from home. The fighting was intense. He was near the rear of his group. He was in a gallop and thought that they had cleared the fighting. Then, he noticed a lone Union soldier by a tree taking aim at him. He had only enough time to draw his firearm and fire. However, the enemy had already pulled the trigger. Monroe Bailiff felt the bullet go through his cartridge box and hit his rib. He never knew if he struck the Union soldier. His mare panicked. She was wounded, and he tried running her into the trees to slow her down and stop. Monroe told that his unit left him behind wounded and with his brother, Columbus, who was sick with Typhoid fever. A local family took them in. During the following weeks, he took the mare and washed her wound at a nearby spring until well.

In December after the battle in September, Monroe and Columbus were captured by Union troops. They were taken to Chattanooga, then to Nashville, and eventually to Louisville, Kentucky. Columbus was still very ill with Typhoid during the trip and languished greatly. After their release in the spring of 1864, they slowly made their way back home to DeKalb County. Monroe was in poor health and unable to perform further military service to the Confederacy.

Just prior to the battle at Chickamauga, Monroe along with Allison’s Cavalry was engaged in the skirmish known locally as the Battle of Snow Hill on April 3, 1863. The battle involved some 2,000 Confederates with an equal number of Union troops. The skirmish actually brought Monroe within a mile of the farm (J.M. Bailiff Farm) in Possum Hollow that he would later purchase and make his home.

Monroe met a young woman and married her on October 6, 1865. Eliza Foster was from the neighboring community of Wolf Creek. They made their home there. And, her father, John M. Foster, gave Eliza a young colored girl as a wedding gift to aid her as a new bride in housekeeping. As the war was over by this time and slavery ended, the colored girl stayed only a short time before leaving.

With three small children, Monroe and Eliza purchased the farm (J.M.Bailiff Farm) in Possum Hollow on September 1, 1875. The farm was a modest hillside farm of some 52 ½ surveyed acres. The survey was completed at a cost of $3.50 on January 26, 1875.

The farmland had not been cleared and was mostly woods. A rock springhouse was complete, as well as, a corral for the animals. The beginnings of a log home were evident, and Monroe set about its completion right away. He built a small one-room log structure with a loft. A frame kitchen was added to the back of the home some years later. He hired a colored man to construct a rock fence on the upper side of the home site as he feared a land slide from the steep hills. The lower side boundary was a small spring-fed stream called Barnes Branch.

Monroe took to the task of clearing the land for crops with a team of oxen. An oxen yoke from this period is still in the possession of the Bailiff family. The primary crops of those early years were wheat and corn. The family was typical of farm families of the era. Cattle, a mule or two, along with the oxen, some poultry and hogs took up residence at the farm. Beekeeping was also a part of the early farm life. They were work animals, produced marketable offspring or goods, or became food for the family.

Monroe’s son, Alonzo Bailiff (1870-1961), told in an interview in 1960 at age 90 that only two families lived in Possum Hollow when his father purchased the farm. They were the Alexander and Braswell families. The home sites where generally surrounded by cane breaks and cattle would run wild there. During hog killing time, wolves would howl at night near the homes. Squirrels were plentiful. On occasion, a 2 or 3 acre plot of corn would have to be guarded or the squirrels would eat every ear. Monroe would hunt wild boars and owned a dog that would catch them.

Eliza Bailiff spun and wove. The women folk would carry water in pig skins. The men had flint rock guns with powder pouches. Small black bears were commonly seen in the hollow, as well as, wild turkeys and pigeons. A few deer where killed from time to time, but are more plentiful now than then.

The Bailiff children of the 1880’s attended school in a small building constructed for that purpose on the grounds owned in recent times by Bob Earl Fuson on the lower end of Possum Hollow. The children’s education ceased upon completion of the 8th grade. However, they received an adequate basic education for the time. A small Baptist congregation that would later become Dry Creek Missionary Baptist Church also used the building. Monroe was one of their early deacons.

Possum Hollow is a part of the greater Dry Creek community on the lower end and a part of the Snow Hill community on the upper end. Alonzo Bailiff mentions in his interview that Dr. Fuson lived in the Dry Creek community and provided medical care for the families in Possum Hollow. Kent Cathcart owned a general store. Daniel Moses operated the Cripps Mill. Jimmy Snow was a local minister as well as a Bro. Lewis.

Entertainment of the day included attending dances and log-rollings. John McDowell was a talented fiddler as well as Elisha Vandergriff who was blind. Making and drinking whiskey was commonplace, however very few were drunks. And, mail was delivered to the Youngblood post office.

The Atwell schoolhouse was a log structure across the road to the east of the more recent Snow Hill school. It had planks in the wall used for a writing table. A wounded Confederate soldier was laid on the writing table during the Battle of Snow Hill and the blood permanently stained the planks. The soldier died and is buried nearby in what is now known as the Mike Clayborn home.

The Lebanon-to-Smithville turnpike ran up Dry Creek, then up and past the Atwell School during the 1860’s. Not until after the War for Southern Independence was the route completed on Snow Hill and diverted away from Dry Creek.

Monroe Bailiff and his family weren’t immune to community controversy. During the 1880’s a neighbor, Pierce Kerley, was calling on a young widow who lived on the ridge above the Bailiff farm. Another man, Tom Bennett, was also calling on the same young widow. After a short altercation at the widow’s home, Pierce shot and killed Tom Bennett.

Monroe Bailiff was plowing in the field and heard the shot. After several minutes had passed, Monroe witnessed Pierce Kerley walk down from the ridge and pass by his home. He stopped by the springhouse and took a drink of the cool spring water using a gourd that Eliza Bailiff kept there. Monroe returned to his plowing as Pierce continued on his way toward his own home. Monroe learned later of the shooting and death of neighbor, Tom Bennett. Pierce was tried and convicted of the murder and sentenced to 10 years in prison. However, before the sentence was carried out he was granted a new trial.

Pierce decided that it was best to leave the area and start a new life elsewhere. This decision had a profound effect on Monroe and Eliza Bailiff. Their daughter, Nancy, had married Pierce Kerley’s stepson, Isaac Cummings. Pierce and his family, along with Isaac Cummings and wife, Nancy Bailiff, left Possum Hollow for Blue Ridge, Texas. While separation was not uncommon for these pioneering families, the effect was still heartbreaking for Monroe and Eliza.

Also heartbreaking for Monroe and Eliza was the accidental drowning of their eight-year-old son, Robert, in 1881. Only a brief note among family papers documents the fact of this occurrence.

During the early years of the J.M. Bailiff farm, oxen were the primary work animals. They were plentiful and more common than the mule. Monroe had worked with oxen his entire life and was very comfortable farming with them. During the decade following the purchase of the farm, the oxen were gradually sold and replaced with mules. Mules were being promoted prior to the War for Southern Independence, but didn’t really grow in numbers until afterwards.

Mules were well suited for the hillside farming found in Possum Hollow. With the use of plows, the mules worked the same long hours as Monroe and his young sons turning the soil for corn and wheat production. The workday generally began at daylight and ended at dark. The work was long and hard.

Mules were also used in the preparation of molasses. Entire families would gather on the upper end of the hollow at “the sugar camp”. Cane was gathered and used in the production of the molasses. While mules would turn the cane mill, the men would gather the juice for cooking. Teenagers and young children would carry away the spent cane. The women would prepare meals for the men. This process often took an entire weekend, day and night, and was a family affair.

By the end of the nineteenth century, steam tractors and crude gasoline tractors were growing in popularity. However due to the steep hillsides of Possum Hollow, tractors were much too dangerous for use. Well into the 1980’s, mules were used for farming in much the same methods as Monroe Bailiff used a hundred years earlier.

Monroe’s son, Leslie Dee Bailiff (1884-1969, 2nd owner J.M. Bailiff farm), told that on the western boundary of the farm a rock fence was started by a neighbor but never finished due to the passing of fencing laws during Reconstruction. This partial rock fence still exists today.

The farm consisted of a number of cattle. Some were butchered to provide meat for the family and others sold. A couple of good milk cows were present and had to be milked daily. Placing the milk in the cool spring water of the rock springhouse provided primitive refrigeration. Poultry provided eggs and meat. Eggs were often sold or traded to traveling peddlers in later years.

Monroe Bailiff was a proficient blacksmith as was his father and grandfather. He was well known in the community for fitting shoes to horses and other work. A recent metal detecting hobbyist found numerous square nails around the yard of the old homestead site. He was also known for his cobbler work. He was skillful at working the leather, making and repairing shoes.

During the period following the War Between the States known as the Reconstruction period, Monroe and Eliza raised nine children. Their firstborn, a daughter, Zanie, died as an infant. The eldest son was William Monroe Bailiff. Bill Bailiff gained an education and was a local school teacher for a time. He and his wife ran a hotel in the Hot Springs, Arkansas area for a few years at the turn of the century. Then later, he moved to Nashville, TN and ran a mail-order goods store. Their son, Alonzo Bailiff, purchased a neighboring farm and lived there with his family for most of his life. Son, Robert, drown at age 8 in 1881. Their daughter, Fannie, married and moved to Nashville with her husband. And, daughter, Nancy moved to Texas with her in-laws, the Kerley family. Monroe and Eliza’s son, Theo, lived his later years in nearby Dowelltown. The youngest son, Edgar, died of pneumonia in 1900 at the age of 13. Son, Leslie Dee Bailiff, purchased the farm from his father and farmed it until the middle of the next century when it passed to the next generation.

The War Between the States was a defining moment in our history. The war changed the South permanently. The years following the war, the Reconstruction years, many young men set out to establish homes and make a living. Monroe Bailiff was one of those young men. The character and integrity of the early farm founders still exist today in their descendents. Although Monroe Bailiff never knew himself as a founder of a Tennessee Century Farm, his legacy and the legacies of those like him will carry on.

written by Kevin Bandy for the Tennessee Century Farm Program